15. Likelihood Ratio Processes and Bayesian Learning#

15.1. Overview#

This lecture describes the role that likelihood ratio processes play in Bayesian learning.

As in this lecture, we’ll use a simple statistical setting from this lecture.

We’ll focus on how a likelihood ratio process and a prior probability determine a posterior probability.

We’ll derive a convenient recursion for today’s posterior as a function of yesterday’s posterior and today’s multiplicative increment to a likelihood process.

We’ll also present a useful generalization of that formula that represents today’s posterior in terms of an initial prior and today’s realization of the likelihood ratio process.

We’ll study how, at least in our setting, a Bayesian eventually learns the probability distribution that generates the data, an outcome that rests on the asymptotic behavior of likelihood ratio processes studied in this lecture.

We’ll also drill down into the psychology of our Bayesian learner and study dynamics under his subjective beliefs.

This lecture provides technical results that underly outcomes to be studied in this lecture and this lecture and this lecture.

We’ll begin by loading some Python modules.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (11, 5) #set default figure size

import numpy as np

from numba import vectorize, njit, prange

from math import gamma

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

colors = sns.color_palette()

@njit

def set_seed():

np.random.seed(142857)

set_seed()

15.2. The Setting#

We begin by reviewing the setting in this lecture, which we adopt here too.

A nonnegative random variable \(W\) has one of two probability density functions, either \(f\) or \(g\).

Before the beginning of time, nature once and for all decides whether she will draw a sequence of IID draws from \(f\) or from \(g\).

We will sometimes let \(q\) be the density that nature chose once and for all, so that \(q\) is either \(f\) or \(g\), permanently.

Nature knows which density it permanently draws from, but we the observers do not.

We do know both \(f\) and \(g\), but we don’t know which density nature chose.

But we want to know.

To do that, we use observations.

We observe a sequence \(\{w_t\}_{t=1}^T\) of \(T\) IID draws from either \(f\) or \(g\).

We want to use these observations to infer whether nature chose \(f\) or \(g\).

A likelihood ratio process is a useful tool for this task.

To begin, we define the key component of a likelihood ratio process, namely, the time \(t\) likelihood ratio as the random variable

We assume that \(f\) and \(g\) both put positive probabilities on the same intervals of possible realizations of the random variable \(W\).

That means that under the \(g\) density, \(\ell (w_t)= \frac{f\left(w_{t}\right)}{g\left(w_{t}\right)}\) is evidently a nonnegative random variable with mean \(1\).

A likelihood ratio process for sequence \(\left\{ w_{t}\right\} _{t=1}^{\infty}\) is defined as

where \(w^t=\{ w_1,\dots,w_t\}\) is a history of observations up to and including time \(t\).

Sometimes for shorthand we’ll write \(L_t = L(w^t)\).

Notice that the likelihood process satisfies the recursion or multiplicative decomposition

The likelihood ratio and its logarithm are key tools for making inferences using a classic frequentist approach due to Neyman and Pearson [NP33].

We’ll again deploy the following Python code from this lecture that evaluates \(f\) and \(g\) as two different beta distributions, then computes and simulates an associated likelihood ratio process by generating a sequence \(w^t\) from some probability distribution, for example, a sequence of IID draws from \(g\).

# Parameters in the two beta distributions.

F_a, F_b = 1, 1

G_a, G_b = 3, 1.2

@vectorize

def p(x, a, b):

r = gamma(a + b) / (gamma(a) * gamma(b))

return r * x** (a-1) * (1 - x) ** (b-1)

# The two density functions.

f = njit(lambda x: p(x, F_a, F_b))

g = njit(lambda x: p(x, G_a, G_b))

@njit

def simulate(a, b, T=50, N=500):

'''

Generate N sets of T observations of the likelihood ratio,

return as N x T matrix.

'''

l_arr = np.empty((N, T))

for i in range(N):

for j in range(T):

w = np.random.beta(a, b)

l_arr[i, j] = f(w) / g(w)

return l_arr

We’ll also use the following Python code to prepare some informative simulations

l_arr_g = simulate(G_a, G_b, N=50000)

l_seq_g = np.cumprod(l_arr_g, axis=1)

l_arr_f = simulate(F_a, F_b, N=50000)

l_seq_f = np.cumprod(l_arr_f, axis=1)

15.3. Likelihood Ratio Process and Bayes’ Law#

Let \(\pi_t\) be a Bayesian posterior defined as

The likelihood ratio process is a principal actor in the formula that governs the evolution of the posterior probability \(\pi_t\), an instance of Bayes’ Law.

Bayes’ law implies that \(\{\pi_t\}\) obeys the recursion

with \(\pi_{0}\) being a Bayesian prior probability that \(q = f\), i.e., a personal or subjective belief about \(q\) based on our having seen no data.

Below we define a Python function that updates belief \(\pi\) using likelihood ratio \(\ell\) according to recursion (15.1)

@njit

def update(π, l):

"Update π using likelihood l"

# Update belief

π = π * l / (π * l + 1 - π)

return π

Formula (15.1) can be generalized by iterating on it and thereby deriving an expression for the time \(t\) posterior \(\pi_{t+1}\) as a function of the time \(0\) prior \(\pi_0\) and the likelihood ratio process \(L(w^{t+1})\) at time \(t\).

To begin, notice that the updating rule

implies

Therefore

Since \(\pi_{0}\in\left(0,1\right)\) and \(L\left(w^{t+1}\right)>0\), we can verify that \(\pi_{t+1}\in\left(0,1\right)\).

After rearranging the preceding equation, we can express \(\pi_{t+1}\) as a function of \(L\left(w^{t+1}\right)\), the likelihood ratio process at \(t+1\), and the initial prior \(\pi_{0}\)

Formula (15.2) generalizes formula (15.1).

Formula (15.2) can be regarded as a one step revision of prior probability \(\pi_0\) after seeing the batch of data \(\left\{ w_{i}\right\} _{i=1}^{t+1}\).

Formula (15.2) shows the key role that the likelihood ratio process \(L\left(w^{t+1}\right)\) plays in determining the posterior probability \(\pi_{t+1}\).

Formula (15.2) is the foundation for the insight that, because of how the likelihood ratio process behaves as \(t \rightarrow + \infty\), the likelihood ratio process dominates the initial prior \(\pi_0\) in determining the limiting behavior of \(\pi_t\).

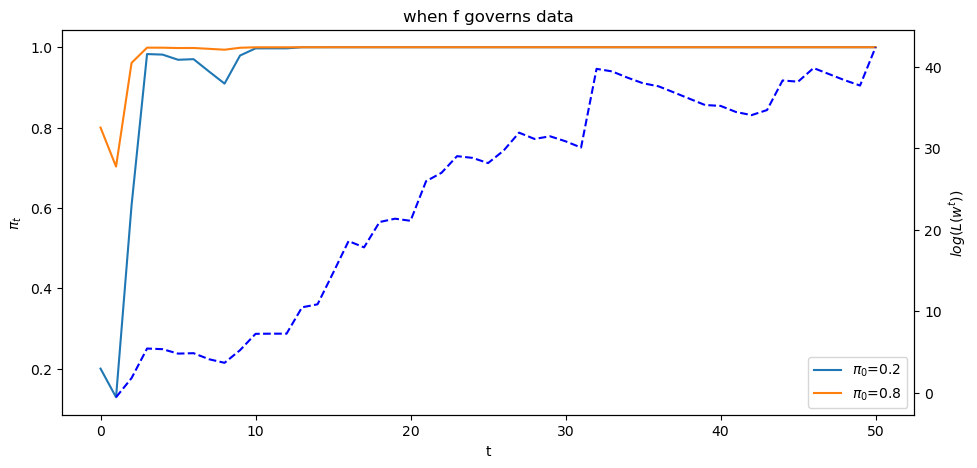

To illustrate this insight, below we will plot graphs showing one simulated path of the likelihood ratio process \(L_t\) along with two paths of \(\pi_t\) that are associated with the same realization of the likelihood ratio process but different initial prior probabilities \(\pi_{0}\).

First, we tell Python two values of \(\pi_0\).

π1, π2 = 0.2, 0.8

Next we generate paths of the likelihood ratio process \(L_t\) and the posterior \(\pi_t\) for a history of IID draws from density \(f\).

T = l_arr_f.shape[1]

π_seq_f = np.empty((2, T+1))

π_seq_f[:, 0] = π1, π2

for t in range(T):

for i in range(2):

π_seq_f[i, t+1] = update(π_seq_f[i, t], l_arr_f[0, t])

fig, ax1 = plt.subplots()

for i in range(2):

ax1.plot(range(T+1), π_seq_f[i, :], label=f"$\pi_0$={π_seq_f[i, 0]}")

ax1.set_ylabel("$\pi_t$")

ax1.set_xlabel("t")

ax1.legend()

ax1.set_title("when f governs data")

ax2 = ax1.twinx()

ax2.plot(range(1, T+1), np.log(l_seq_f[0, :]), '--', color='b')

ax2.set_ylabel("$log(L(w^{t}))$")

plt.show()

The dotted line in the graph above records the logarithm of the likelihood ratio process \(\log L(w^t)\).

Please note that there are two different scales on the \(y\) axis.

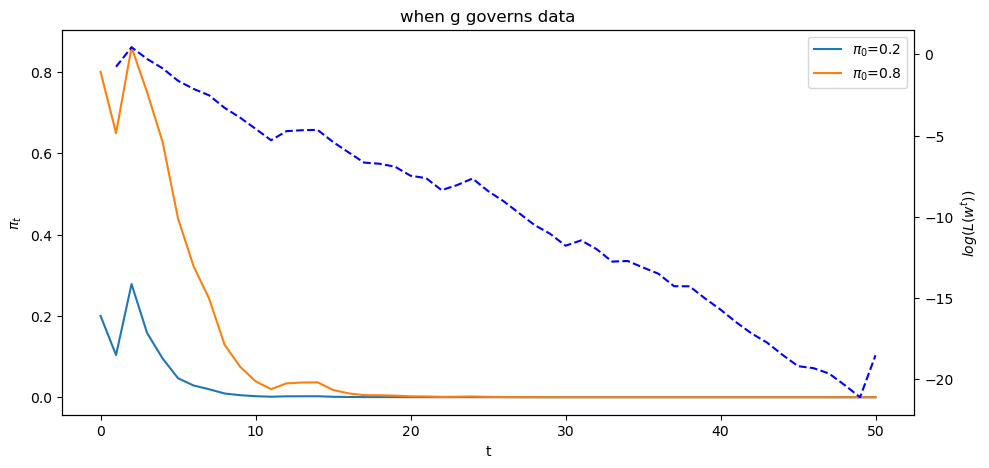

Now let’s study what happens when the history consists of IID draws from density \(g\)

T = l_arr_g.shape[1]

π_seq_g = np.empty((2, T+1))

π_seq_g[:, 0] = π1, π2

for t in range(T):

for i in range(2):

π_seq_g[i, t+1] = update(π_seq_g[i, t], l_arr_g[0, t])

fig, ax1 = plt.subplots()

for i in range(2):

ax1.plot(range(T+1), π_seq_g[i, :], label=f"$\pi_0$={π_seq_g[i, 0]}")

ax1.set_ylabel("$\pi_t$")

ax1.set_xlabel("t")

ax1.legend()

ax1.set_title("when g governs data")

ax2 = ax1.twinx()

ax2.plot(range(1, T+1), np.log(l_seq_g[0, :]), '--', color='b')

ax2.set_ylabel("$log(L(w^{t}))$")

plt.show()

Below we offer Python code that verifies that nature chose permanently to draw from density \(f\).

π_seq = np.empty((2, T+1))

π_seq[:, 0] = π1, π2

for i in range(2):

πL = π_seq[i, 0] * l_seq_f[0, :]

π_seq[i, 1:] = πL / (πL + 1 - π_seq[i, 0])

np.abs(π_seq - π_seq_f).max() < 1e-10

True

We thus conclude that the likelihood ratio process is a key ingredient of the formula (15.2) for a Bayesian’s posteior probabilty that nature has drawn history \(w^t\) as repeated draws from density \(g\).

15.4. Behavior of posterior probability \(\{\pi_t\}\) under the subjective probability distribution#

We’ll end this lecture by briefly studying what our Baysian learner expects to learn under the subjective beliefs \(\pi_t\) cranked out by Bayes’ law.

This will provide us with some perspective on our application of Bayes’s law as a theory of learning.

As we shall see, at each time \(t\), the Bayesian learner knows that he will be surprised.

But he expects that new information will not lead him to change his beliefs.

And it won’t on average under his subjective beliefs.

We’ll continue with our setting in which a McCall worker knows that successive draws of his wage are drawn from either \(F\) or \(G\), but does not know which of these two distributions nature has drawn once-and-for-all before time \(0\).

We’ll review and reiterate and rearrange some formulas that we have encountered above and in associated lectures.

The worker’s initial beliefs induce a joint probability distribution over a potentially infinite sequence of draws \(w_0, w_1, \ldots \).

Bayes’ law is simply an application of laws of probability to compute the conditional distribution of the \(t\)th draw \(w_t\) conditional on \([w_0, \ldots, w_{t-1}]\).

After our worker puts a subjective probability \(\pi_{-1}\) on nature having selected distribution \(F\), we have in effect assumes from the start that the decision maker knows the joint distribution for the process \(\{w_t\}_{t=0}\).

We assume that the worker also knows the laws of probability theory.

A respectable view is that Bayes’ law is less a theory of learning than a statement about the consequences of information inflows for a decision maker who thinks he knows the truth (i.e., a joint probability distribution) from the beginning.

15.4.1. Mechanical details again#

At time \(0\) before drawing a wage offer, the worker attaches probability \(\pi_{-1} \in (0,1)\) to the distribution being \(F\).

Before drawing a wage at time \(0\), the worker thus believes that the density of \(w_0\) is

Let \(a \in \{ f, g\} \) be an index that indicates whether nature chose permanently to draw from distribution \(f\) or from distribution \(g\).

After drawing \(w_0\), the worker uses Bayes’ law to deduce that the posterior probability \(\pi_0 = {\rm Prob}{a = f | w_0} \) that the density is \(f(w)\) is

More generally, after making the \(t\)th draw and having observed \(w_t, w_{t-1}, \ldots, w_0\), the worker believes that the probability that \(w_{t+1}\) is being drawn from distribution \(F\) is

or

and that the density of \(w_{t+1}\) conditional on \(w_t, w_{t-1}, \ldots, w_0\) is

Notice that

so that the process \(\pi_t\) is a martingale.

Indeed, it is a bounded martingale because each \(\pi_t\), being a probability, is between \(0\) and \(1\).

In the first line in the above string of equalities, the term in the first set of brackets is just \(\pi_t\) as a function of \(w_{t}\), while the term in the second set of brackets is the density of \(w_{t}\) conditional on \(w_{t-1}, \ldots , w_0\) or equivalently conditional on the sufficient statistic \(\pi_{t-1}\) for \(w_{t-1}, \ldots , w_0\).

Notice that here we are computing \(E(\pi_t | \pi_{t-1})\) under the subjective density described in the second term in brackets.

Because \(\{\pi_t\}\) is a bounded martingale sequence, it follows from the martingale convergence theorem that \(\pi_t\) converges almost surely to a random variable in \([0,1]\).

Practically, this means that probability one is attached to sample paths \(\{\pi_t\}_{t=0}^\infty\) that converge.

According to the theorem, it different sample paths can converge to different limiting values.

Thus, let \(\{\pi_t(\omega)\}_{t=0}^\infty\) denote a particular sample path indexed by a particular \(\omega \in \Omega\).

We can think of nature as drawing an \(\omega \in \Omega\) from a probability distribution \({\textrm{Prob}} \Omega\) and then generating a single realization (or simulation) \(\{\pi_t(\omega)\}_{t=0}^\infty\) of the process.

The limit points of \(\{\pi_t(\omega)\}_{t=0}^\infty\) as \(t \rightarrow +\infty\) are realizations of a random variable that is swept out as we sample \(\omega\) from \(\Omega\) and construct repeated draws of \(\{\pi_t(\omega)\}_{t=0}^\infty\).

By staring at law of motion (15.1) or (15.3) , we can figure out some things about the probability distribution of the limit points

Evidently, since the likelihood ratio \(\ell(w_t) \) differs from \(1\) when \(f \neq g\), as we have assumed, the only possible fixed points of (15.3) are

and

Thus, for some realizations, \(\lim_{\rightarrow + \infty} \pi_t(\omega) =1\) while for other realizations, \(\lim_{\rightarrow + \infty} \pi_t(\omega) =0\).

Now let’s remember that \(\{\pi_t\}_{t=0}^\infty\) is a martingale and apply the law of iterated expectations.

The law of iterated expectations implies

and in particular

Applying the above formula to \(\pi_\infty\), we obtain

where the mathematical expectation \(E_{-1}\) here is taken with respect to the probability measure \({\textrm{Prob}(\Omega)}\).

Since the only two values that \(\pi_\infty(\omega)\) can take are \(1\) and \(0\), we know that for some \(\lambda \in [0,1]\)

and consequently that

Combining this equation with equation (20), we deduce that the probability that \({\textrm{Prob}(\Omega)}\) attaches to \(\pi_\infty(\omega)\) being \(1\) must be \(\pi_{-1}\).

Thus, under the worker’s subjective distribution, \(\pi_{-1}\) of the sample paths of \(\{\pi_t\}\) will converge pointwise to \(1\) and \(1 - \pi_{-1}\) of the sample paths will converge pointwise to \(0\).

15.4.2. Some simulations#

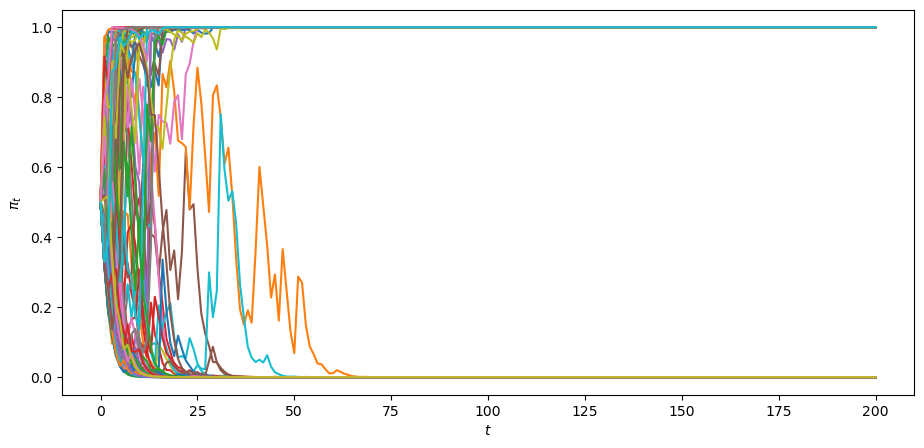

Let’s watch the martingale convergence theorem at work in some simulations of our learning model under the worker’s subjective distribution.

Let us simulate \(\left\{ \pi_{t}\right\} _{t=0}^{T}\), \(\left\{ w_{t}\right\} _{t=0}^{T}\) paths where for each \(t\geq0\), \(w_t\) is drawn from the subjective distribution

We’ll plot a large sample of paths.

@njit

def martingale_simulate(π0, N=5000, T=200):

π_path = np.empty((N,T+1))

w_path = np.empty((N,T))

π_path[:,0] = π0

for n in range(N):

π = π0

for t in range(T):

# draw w

if np.random.rand() <= π:

w = np.random.beta(F_a, F_b)

else:

w = np.random.beta(G_a, G_b)

π = π*f(w)/g(w)/(π*f(w)/g(w) + 1 - π)

π_path[n,t+1] = π

w_path[n,t] = w

return π_path, w_path

def fraction_0_1(π0, N, T, decimals):

π_path, w_path = martingale_simulate(π0, N=N, T=T)

values, counts = np.unique(np.round(π_path[:,-1], decimals=decimals), return_counts=True)

return values, counts

def create_table(π0s, N=10000, T=500, decimals=2):

outcomes = []

for π0 in π0s:

values, counts = fraction_0_1(π0, N=N, T=T, decimals=decimals)

freq = counts/N

outcomes.append(dict(zip(values, freq)))

table = pd.DataFrame(outcomes).sort_index(axis=1).fillna(0)

table.index = π0s

return table

# simulate

T = 200

π0 = .5

π_path, w_path = martingale_simulate(π0=π0, T=T, N=10000)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

for i in range(100):

ax.plot(range(T+1), π_path[i, :])

ax.set_xlabel('$t$')

ax.set_ylabel('$\pi_t$')

plt.show()

The above graph indicates that

each of paths converges

some of the paths converge to \(1\)

some of the paths converge to \(0\)

none of the paths converge to a limit point not equal to \(0\) or \(1\)

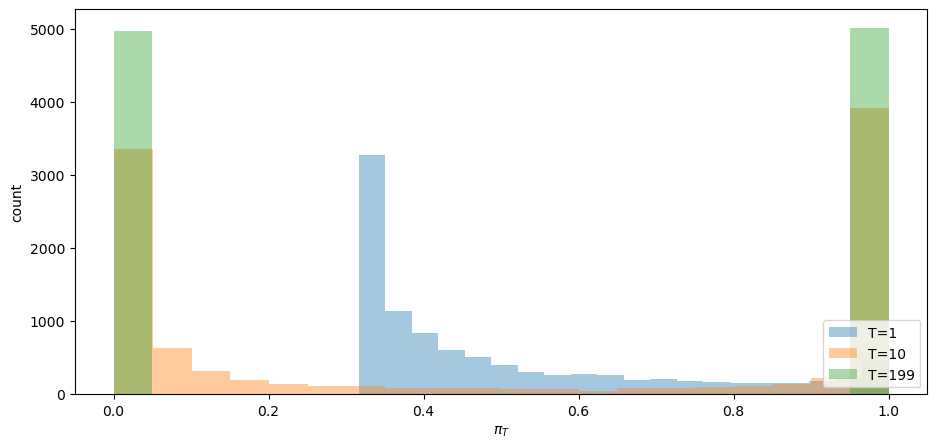

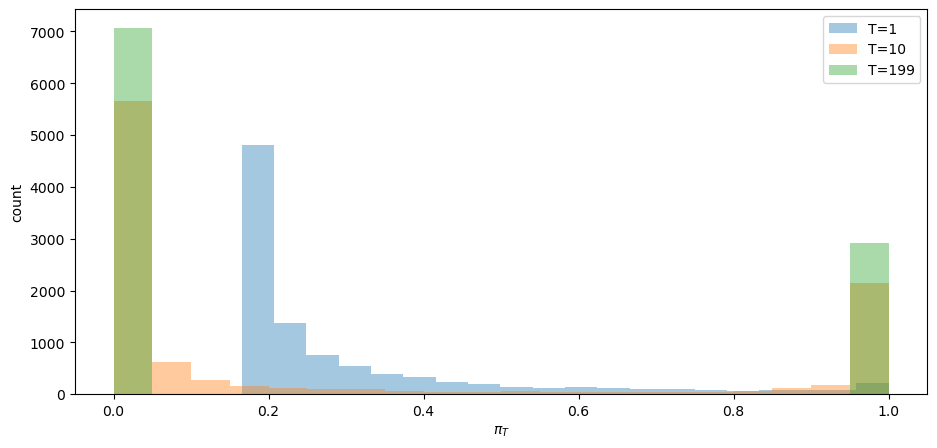

Convergence actually occurs pretty fast, as the following graph of the cross-ensemble distribution of \(\pi_t\) for various small \(t\)’s indicates.

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

for t in [1, 10, T-1]:

ax.hist(π_path[:,t], bins=20, alpha=0.4, label=f'T={t}')

ax.set_ylabel('count')

ax.set_xlabel('$\pi_T$')

ax.legend(loc='lower right')

plt.show()

Evidently, by \(t = 199\), \(\pi_t\) has converged to either \(0\) or \(1\).

The fraction of paths that have converged to \(1\) is \(.5\)

The fractions of paths that have converged to \(0\) is also \(.5\).

Does the fraction \(.5\) ring a bell?

Yes, it does: it equals the value of \(\pi_0 = .5 \) that we used to generate each sequence in the ensemble.

So let’s change \(\pi_0\) to \(.3\) and watch what happens to the distribution of the ensemble of \(\pi_t\)’s for various \(t\)’s.

# simulate

T = 200

π0 = .3

π_path3, w_path3 = martingale_simulate(π0=π0, T=T, N=10000)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

for t in [1, 10, T-1]:

ax.hist(π_path3[:,t], bins=20, alpha=0.4, label=f'T={t}')

ax.set_ylabel('count')

ax.set_xlabel('$\pi_T$')

ax.legend(loc='upper right')

plt.show()

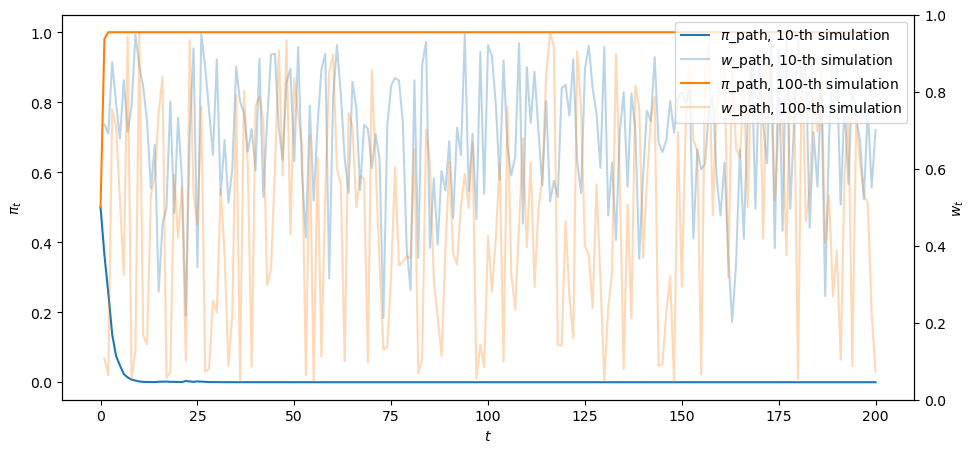

For the preceding ensemble that assumed \(\pi_0 = .5\), the following graph shows two paths of \(w_t\)’s and the \(\pi_t\) sequences that gave rise to them.

Notice that one of the paths involves systematically higher \(w_t\)’s, outcomes that push \(\pi_t\) upward.

The luck of the draw early in a simulation push the subjective distribution to draw from \(F\) more frequently along a sample path, and this pushes \(\pi_t\) toward \(0\).

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

for i, j in enumerate([10, 100]):

ax.plot(range(T+1), π_path[j,:], color=colors[i], label=f'$\pi$_path, {j}-th simulation')

ax.plot(range(1,T+1), w_path[j,:], color=colors[i], label=f'$w$_path, {j}-th simulation', alpha=0.3)

ax.legend(loc='upper right')

ax.set_xlabel('$t$')

ax.set_ylabel('$\pi_t$')

ax2 = ax.twinx()

ax2.set_ylabel("$w_t$")

plt.show()

15.5. Initial Prior is Verified by Paths Drawn from Subjective Conditional Densities#

Now let’s use our Python code to generate a table that checks out our earlier claims about the probability distribution of the pointwise limits \(\pi_{\infty}(\omega)\).

We’ll use our simulations to generate a histogram of this distribution.

In the following table, the left column in bold face reports an assumed value of \(\pi_{-1}\).

The second column reports the fraction of \(N = 10000\) simulations for which \(\pi_{t}\) had converged to \(0\) at the terminal date \(T=500\) for each simulation.

The third column reports the fraction of \(N = 10000\) simulations for which \(\pi_{t}\) had converged to \(1\) as the terminal date \(T=500\) for each simulation.

# create table

table = create_table(list(np.linspace(0,1,11)), N=10000, T=500)

table

| 0.0 | 1.0 | |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 1.0000 | 0.0000 |

| 0.1 | 0.8929 | 0.1071 |

| 0.2 | 0.7994 | 0.2006 |

| 0.3 | 0.7014 | 0.2986 |

| 0.4 | 0.5939 | 0.4061 |

| 0.5 | 0.5038 | 0.4962 |

| 0.6 | 0.3982 | 0.6018 |

| 0.7 | 0.3092 | 0.6908 |

| 0.8 | 0.1963 | 0.8037 |

| 0.9 | 0.0963 | 0.9037 |

| 1.0 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 |

The fraction of simulations for which \(\pi_{t}\) had converged to \(1\) is indeed always close to \(\pi_{-1}\), as anticipated.

15.6. Drilling Down a Little Bit#

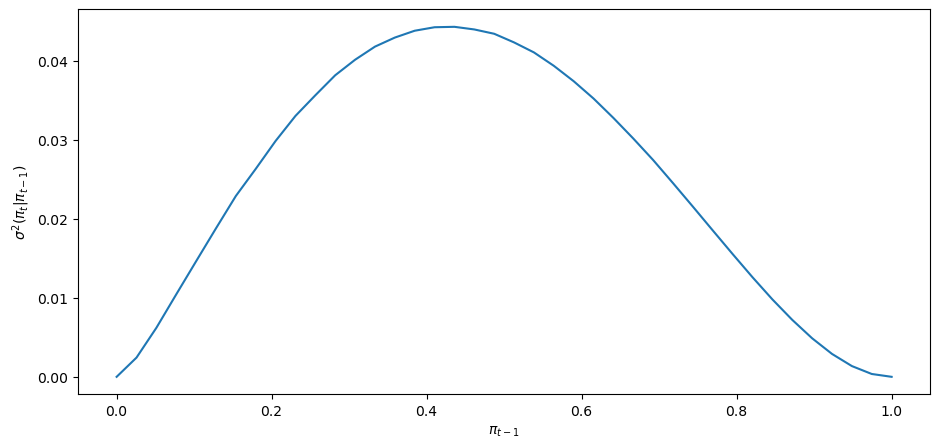

To understand how the local dynamics of \(\pi_t\) behaves, it is enlightening to consult the variance of \(\pi_{t}\) conditional on \(\pi_{t-1}\).

Under the subjective distribution this conditional variance is defined as

We can use a Monte Carlo simulation to approximate this conditional variance.

We approximate it for a grid of points \(\pi_{t-1} \in [0,1]\).

Then we’ll plot it.

@njit

def compute_cond_var(pi, mc_size=int(1e6)):

# create monte carlo draws

mc_draws = np.zeros(mc_size)

for i in prange(mc_size):

if np.random.rand() <= pi:

mc_draws[i] = np.random.beta(F_a, F_b)

else:

mc_draws[i] = np.random.beta(G_a, G_b)

dev = pi*f(mc_draws)/(pi*f(mc_draws) + (1-pi)*g(mc_draws)) - pi

return np.mean(dev**2)

pi_array = np.linspace(0, 1, 40)

cond_var_array = []

for pi in pi_array:

cond_var_array.append(compute_cond_var(pi))

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(pi_array, cond_var_array)

ax.set_xlabel('$\pi_{t-1}$')

ax.set_ylabel('$\sigma^{2}(\pi_{t}\\vert \pi_{t-1})$')

plt.show()

The shape of the the conditional variance as a function of \(\pi_{t-1}\) is informative about the behavior of sample paths of \(\{\pi_t\}\).

Notice how the conditional variance approaches \(0\) for \(\pi_{t-1}\) near either \(0\) or \(1\).

The conditional variance is nearly zero only when the agent is almost sure that \(w_t\) is drawn from \(F\), or is almost sure it is drawn from \(G\).

15.7. Sequels#

This lecture has been devoted to building some useful infrastructure that will help us understand inferences that are the foundations of results described in this lecture and this lecture and this lecture.